All four were entirely believable: they had rapport between themselves and built a strong relationship with the audience which came across even on the screen. Two casts of actors are used in the production so that if one ‘bubble’ has to isolate, the show will go on.

So the play deals with heavy matters but it does so with humour, tenderness and dramatic prowess which are fully and entertainingly exploited by Ayckbourn’s own direction. For example, Rob and Alex, armed with some internet research into events of the war, wonder if they can warn Lily and Alf of impending danger and so save them from tragedy. Ayckbourn creates the plays’ emotional climaxes out of the characters’ concerns for one another – using the timeline as a technical tool to show the universality of human feeling and compassion. With a lightness of touch which nevertheless has impact, Ayckbourn suggests that people were more emotionally and socially reserved in the war years than today, and less selfish.īut, whatever their faults and foibles, the characters begin to care about each other, and we care about them too. The kids survive.” That’s what he’s fighting for. When Alf unexpectedly arrives home on leave, he talks movingly about his fears but says: “What really matters is Lil. As the play progresses, Ayckbourn compares more of the differing social norms and expectations of the two eras. The contrast between Lily’s and Rob’s approaches to straitened circumstances seems to be about more than character. Eventually, she comes out with, “What do you find to do all day?” We, the audience know: Rob spends a lot of the day feeling sorry for himself.

And later, when Rob takes her into his kitchen and introduces her to the dishwasher, the fridge and freezer, she’s struck dumb. She talks of missing her husband, Alf, who’s fighting in North Africa. Lily talks of sharing her rations with friends and family. It’s quite common for comparisons to be made between the Covid pandemic and world wars but Ayckbourn, through the magic of his dramatic imagination, draws us into Lily’s world a world of evacuated children and of air-raids, and makes it live for us. He has walked into 1942, into a world at war.

But when Lily walks out of the room and disappears through an invisible wall, Rob is jolted into realising something more impossible has happened than a global pandemic and his personal misfortune.

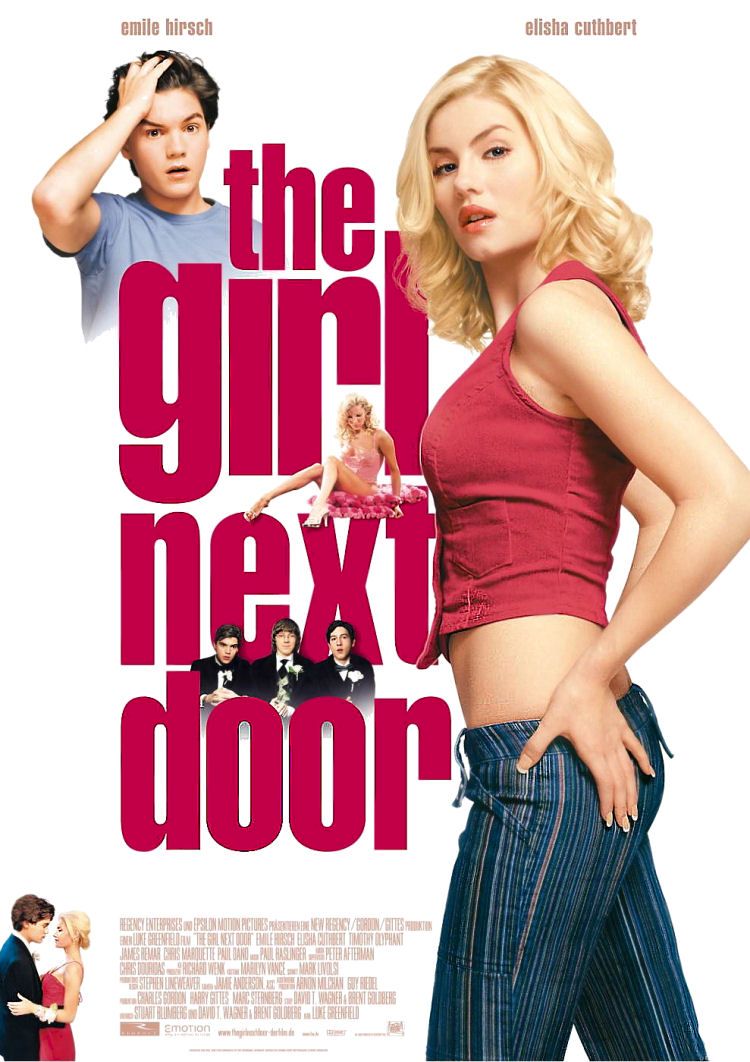

The girl next door tv#

In her kitchen, he thinks the 1940s décor is a TV set: this man is seriously obsessed with himself and his immediate world. When he enters her garden, he doesn’t notice at first the neat vegetable plot that has replaced his neighbours’ lawn. Despite his bruised ego, he’s keen to know an attractive young woman and offers to mend the faulty kitchen tap she mentions. Rob’s confusion turns to disbelief that Lily doesn’t recognise him as the firefighting hero from the popular TV soap he once starred in. But no, Lily Tindall says she’s lived next-door for seven years. He assumes the woman is looking after his neighbours’ house while they spend the pandemic in their second home. So, instead of googling sex toys, he ogles a young woman he’s noticed next door, strolls into his garden and introduces himself over the hedge. Rob’s latest wheeze, to buy a blow-up doll for sexual relief, could be the final straw for Alex. He can find nothing to do in semi-lockdown except irritate his sister, Alex, who’s moved in to support him while she Zoom-works for the government. His dalliances with women destroyed his first marriage, his second wife has left him and his work as an actor has dried up. On stage, the kitchen and garden of each house, separated by a hedge, are shown in contrasting detail.Ħ0 year-old Rob is in a mess. Ayckbourn’s twist is to set one household in the pandemic of 2020 and the other in war-torn 1942 (when the playwright was three years old). The basic idea is simple: take two neighbouring London households on one August day and introduce them to each another. The Girl Next Door is Alan Ayckbourn’s 85th play yet it feels fresh and innovative. If ingenuity, commitment and talent were all it took for theatre to survive this pandemic, we’d be laughing. The camera work was impeccable, taking the screen audience right into the action. It was streamed to my laptop and, with the help of an HDMI lead, screened on my TV. But it wasn’t so terrible after all: thanks to the resourcefulness of the Stephen Joseph Theatre team, I watched a live performance of a world premiere, written and directed by that master of theatre, Alan Ayckbourn. Thwarted, dammit! That’s what I thought when, two days before my first theatre trip in nearly 18 months, I was told to self-isolate.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)